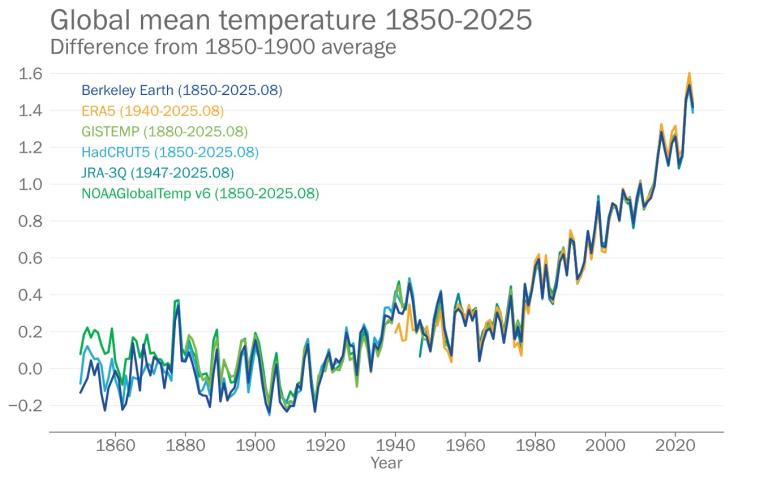

The world is heating up at an alarming rate. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) says that the past 11 years (2015–2025) have been the warmest in recorded history, with 2023, 2024, and 2025 ranking as the three hottest years ever observed.

According to the WMO’s State of the Global Climate Update 2025, the average global temperature between January and August 2025 was 1.42°C above pre-industrial levels. The report paints a troubling picture of record-breaking heat, melting ice, rising sea levels, and more frequent extreme weather events — all accelerating the pace of climate disruption.

WMO scientists say concentrations of greenhouse gases, which trap heat in the atmosphere, reached record highs in 2024 and continued to rise in 2025. Ocean heat content — a key measure of how much heat the Earth system stores — also hit new records.

“This unprecedented streak of high temperatures, combined with last year’s record increase in greenhouse gas levels, makes it clear that it will be virtually impossible to limit global warming to 1.5°C in the next few years without temporarily overshooting this target,” said WMO Secretary-General Celeste Saulo.

“But the science is equally clear — it’s still possible and essential to bring temperatures back down to 1.5°C by the end of the century.”

UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for immediate, large-scale action to minimise damage.

“Each year above 1.5 degrees will hammer economies, deepen inequalities, and inflict irreversible damage,” he said. “We must act now, at great speed and scale, to make the overshoot as small, as short, and as safe as possible.”

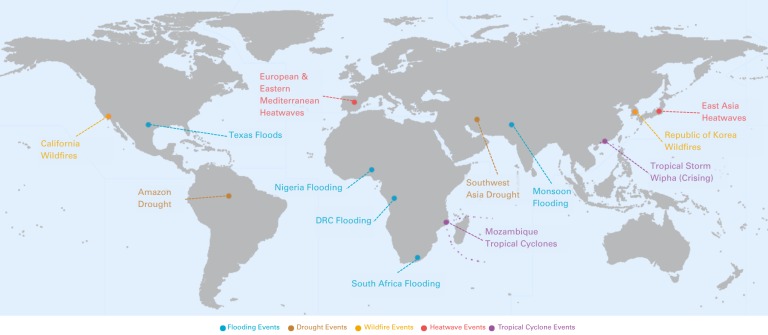

From deadly floods in Africa and Asia to wildfires in North America and Europe, the report says that 2025 has been marked by disasters that have upended lives, displaced millions, and hurt food systems and economies.

Rising global temperatures have caused glaciers to melt, sea levels to climb, and storms to intensify. The impacts are cascading across sectors — from agriculture and energy to health and migration.

The report warns that ocean heat is driving irreversible changes to marine ecosystems, killing coral reefs, reducing biodiversity, and weakening the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide.

Levels of carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O) — the main greenhouse gases — continue to surge.

In 2024, atmospheric CO₂ reached 423.9 parts per million (ppm) — 53% higher than pre-industrial levels. The increase from 2023 to 2024 was the largest ever recorded at 3.5 ppm.

Methane and nitrous oxide, both powerful heat-trapping gases, also reached record highs, further driving global warming.

Over 90% of excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases is absorbed by the oceans. The ocean heat content surpassed all previous records, showing the world’s waters are accumulating energy faster than ever before.

This heating, scientists warn, is causing: stronger tropical storms and cyclones, faster melting of sea ice, rising sea levels, and long-term changes that are irreversible for centuries or even millennia.

The record-breaking global heat of 2024 pushed global energy demand 4% higher than the 1991–2020 average.

In Central and Southern Africa, demand rose nearly 30%, showing how rising temperatures are straining energy systems, especially in developing regions. The WMO says integrating climate data into renewable energy planning — from solar and wind to hydropower — is now critical to building resilient and flexible energy systems.

The report highlights major progress in early warning systems since 2015. The number of countries with Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems (MHEWS) has more than doubled, from 56 in 2015 to 119 in 2024.

However, 40% of countries still lack such systems. The UN’s “Early Warnings for All” initiative aims for global coverage by 2027, but experts say faster action is needed — especially in Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island States (SIDS).

National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) now play a growing role in national climate policies. Nearly two-thirds of these agencies provide climate services, up from 35% just five years ago.

These include seasonal forecasts, agriculture and water advisories, and heat-health alerts, helping governments and citizens adapt to extreme weather.

The WMO’s State of the Global Climate Update 2025 — released ahead of COP30 in Belém, Brazil — serves as a scientific anchor for climate negotiations.

It reminds world leaders that without immediate action, the Earth is heading toward irreversible climate tipping points. Yet, it also offers a message of hope — that science, data, and coordinated global action can still steer the planet toward recovery.