Christmas has packed its bags and left us with full bellies, stubborn waistlines and a lingering question on the tongue: did the food really taste as good as it used to? I ask because even as Ghana sweeps away the wrappers and fold the tablecloths, the memory of taste refuses to go quietly. And memory, especially food memory, is a dangerous thing. It can turn reasonable adults into grumbling philosophers.

Let me say this upfront: this is not nostalgia doing Hark my Soul. I know nostalgia well; it has a sweet smell and a tendency to exaggerate. This is something else. This is that uncomfortable feeling you get when you take a bite of something you’ve loved for decades and realise – slowly, painfully – that the magic has gone. The trouble is, you don’t know who to complain to. Taste has no customer care desk.

Does consumer rights ring a bell? Today’s article could be a sentimental journey but there are socio-political imperatives too. For instance, what can a nation achieve if it is unable to maintain the taste of its own foods?

Across the decades, Ghanaian food has changed. Or perhaps food has stayed the same and we have changed. Either way, the taste has shifted, slipped, softened, sometimes vanished altogether. And Christmas, of all seasons, exposes it mercilessly.

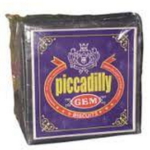

Take biscuits. In a fit of seasonal sentimentality, I recently bought a box of those famous Christmas biscuits whose name rhymes conveniently with crocodilly. I brought it home proudly, only to be met with polite indifference from my 21st-century youngsters and a raised eyebrow from a certain Mrs A. I knew immediately that I was on my own. One bite confirmed my fears. The biscuit was crunchy, yes, but the old taste—the one that made Christmas feel official—was missing. Those big tins used to announce the season before any carols were sung. They were worn as necklaces, hoarded, rationed, and fiercely defended. Today, they are just biscuits.

And then there were Danish cookies. Not these apologetic versions we know now, but the real ones – the kind that arrived with a been-to relative and were opened like a sacred ritual. The aroma filled the room. Those who know, know. Portions were distributed with solemn fairness. In five minutes, it was finished, leaving behind that blue tin which later became a jewellery box, a sewing kit, a toolbox, or a family archive for odd screws. The cookies are still around, but the taste?

Christmas chicken deserves its own obituary. Once upon a time, chicken tasted like chicken. Local or broiler, it didn’t matter. The soup was rich, confident, deeply chickenish—especially when spiced with akukɔ mmensa. This past Christmas, many of us ate chicken out of tradition rather than excitement. Tell me honestly: did your chicken sing, or did it merely speak?

Beyond Christmas, the decline continues. Many years ago, when I was growing up in Accra, food tasted… sincere. Snacks were not aspirational; they were just good. There was Sunspot. There was that golden milk-chocolate goodness in a triangular box that could keep a child on best behaviour for months. Chocolates then were powerful things. They could inspire elaborate schemes, secret savings, and long walks to Kingsway or GNTC. My sister Margaret would save all term long only for me to get her several bars for ‘’Awa Day.’’ Today’s chocolates look impressive, but they don’t quite hit the heart the way the old ones did. Chocolates could make a girl kill (like a James bond 007 female side kick).

Sardines, anyone? Ah. Let us talk about sardines. The day I realised finally that my Kofi Akpabli world is very different from that of my children is that afternoon I got to the chicken sink to see half-eaten sardines among their left-overs. As someone now officially allowed to begin sentences with “in my time,” I can say this: canned sardines used to be an Event. Opening a tin was an announcement to the neighbourhood cats. The fish was firm, flavourful, confident. Sometimes, all you needed was the oil. Mix it with rice and life made sense. Today’s sardines are… present. They exist. Chewing them is a chore; just like watching a black and white movie after the discovery of colour television.

Corned beef – we used to hail it as kona beef—was once a culinary royalty. When a tin was opened, the empty can did not go quietly into the bin. It was displayed proudly on the room divider, evidence that something important had happened in the vicinity. Indeed, how could you prepare corned beef stew without your neighbours nose-ing about it? It was food and status rolled into one. Now, corned beef still fills shelves, but it no longer fills the soul.

Am I allowed to mention the rocky crunchiness of Good Old Milo? Remember Bournvita?

Anyway, our childhood cereals were not boxed; they were brewed. Tom Brown, rice water, kaka oats, (Quaker Oats) oblayo, ekoegbeemi—these were serious breakfasts. A drop of evaporated milk on any of these cereal sensations could turn a bowl into a feast. Milk itself tasted like milk. Today, many brands are just… there. Indeed, powdered milk used to be so good that younger siblings’ Lactogen required active domestic surveillance. Now you know where the concept of CCTV probably came from.

Street snacks have also faded quietly. Achomor, kulikuli, akankyier, agbelikaklo, atsifuifui, joley kaklo, anduuley—these were flavours with personality. Today, many young people cannot tell boflot from togber. As for akpiti, it sounds like a forgotten password. Full meal Waachey survives, yes, but is it the same waachey? The one folded in leaves, crowned with shito and sides, hiding a treasure called kanzo—the burnt rice scraped from the pot and sold like gold. Where did kanzo go? Ask the cyto boys of memory.

Even water has changed. Remember the cooler? That elegant earthenware pot sitting quietly in the corner, producing water that was always cool and mysteriously sweet. Some mothers flavoured the water with some burnt palm nut chaff, turning hydration into an experience. Today we drink “pure water” and argue about brands, but the pleasure is thinner. Once upon a time, water itself could make you pause.

Spices and vegetables have not been spared. Green pepper has lost its perfume. Ginger and garlic no longer announce themselves boldly. Kpakpo shito, once the life of kormi kala is facing an identity crisis. The once famous cherry-like chili now whispers instead of shouting. Is it the fertiliser? Climate change? Speed farming? Or are our tongues simply tired?

I don’t have answers. I only have questions—and a stubborn belief that food deserves respect. Taste matters. It is culture, memory, comfort and joy all rolled into one. As we march forward with better packaging and longer shelf life, perhaps we should ask what we have traded away.

Or perhaps it’s just me, standing at the end of another Christmas, chewing thoughtfully and wondering where did the flavour go?