At a time when most people use keyboards to write, does handwriting really matter?

Yes, say Indian courts, if the writer is a doctor.

Jokes around the notoriously bad handwriting of many doctors that can only be deciphered by pharmacists are common in India, as around the world.

But the latest order emphasising the importance of clear handwriting came recently from the Punjab and Haryana High Court, which said that “legible medical prescription is a fundamental right” as it can make a difference between life and death.

The court order came in a case that had nothing to do with the written word. It involved allegations of rape, cheating and forgery by a woman and Justice Jasgurpreet Singh Puri was hearing the man’s petition for bail.

The woman had alleged that the man had taken money from her, promising her a government job, conducted fake interviews with her and sexually exploited her.

The accused denied the charges – he said they had a consensual relationship, and the case was brought on because of a dispute over money.

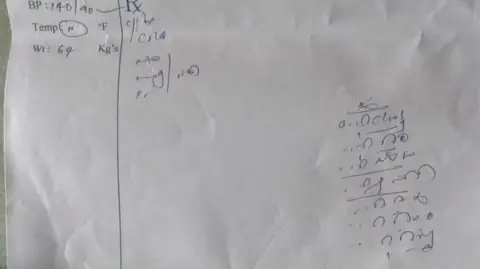

Justice Puri said when he looked at the medico-legal report – written by a government doctor who had examined the woman – he found it incomprehensible.

“It shook the conscience of this court as not even a word or a letter was legible,” he wrote in the order.

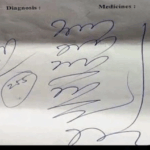

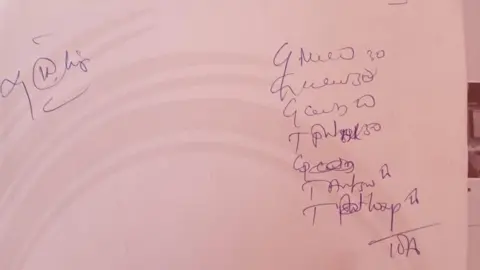

The BBC has seen a copy of the judgement, which includes the report and a two-page prescription which shows the doctor’s unreadable scrawl.

“At a time when technology and computers are easily accessible, it is shocking that government doctors are still writing prescriptions by hand, which cannot be read by anybody except perhaps some chemists,” Justice Puri wrote.

The court asked the government to include handwriting lessons in the medical school curriculum and set a two-year timeline for rolling out digitised prescriptions.

Until that happens, all doctors must write prescriptions clearly in capital letters, Justice Puri said.

Dr Dilip Bhanushali, president of the Indian Medical Association, which has more than 330,000 doctors as members, told the BBC that they’re willing to help find a solution to the problem.

In cities and bigger towns, he says, doctors have moved to digital prescriptions, but it’s very difficult in rural areas and small towns to get prescriptions that are clear.

“It’s a well-known fact that many doctors have poor handwriting, but that’s because most medical practitioners are very busy, especially in overcrowded government hospitals,” he says.

“We have recommended to our members to follow the government guidelines and write prescriptions in bold letters that should be readable to both patients and chemists. A doctor who sees seven patients a day can do it, but if you see 70 patients a day, you can’t do it,” he adds.

This is not the first time an Indian court has called out the sloppy handwriting of doctors. Past instances include the high court in Odisha state, which flagged “the zigzag style of writing by doctors” and judges in the Allahabad high court who lamented about “reports written in such shabby handwriting that they are not decipherable”.

Studies, however, have failed to support the conventional wisdom that doctors’ handwriting is worse than others.

But experts say emphasis on their handwriting is not about aesthetics or convenience but a medical prescription that leaves room for ambiguity or misinterpretation can have serious – even tragic – consequences.

According to a 1999 report by the Institute of Medicine (IoM), medical errors caused at least an estimated 44,000 preventable deaths annually in the US, of which 7,000 were attributable to sloppy handwriting.

More recently, in Scotland, a woman suffered chemical injuries after she was mistakenly given erectile dysfunction cream for a dry eye condition.

Health authorities in the UK have admitted that “drug errors caused appalling levels of harm and deaths” and added that “roll out of electronic prescribing systems across more hospitals could reduce errors by 50%”.

India does not have robust data on harm caused by poor handwriting, but in the world’s most populous country misreading of prescriptions in the past has resulted in health emergencies and many deaths.

There’s this reported case of a woman who suffered from convulsions after taking a medicine for diabetes which had a similar-sounding name to an analgesic she had been prescribed.

Chilukuri Paramathama, who runs a pharmacy in Nalgonda city in the southern Indian state of Telangana, told the BBC that in 2014, he filed a public interest petition in the high court in Hyderabad after reading news reports about a three-year-old who had died in Noida city after she was administered a wrong injection for fever.

His campaign, seeking a complete ban on handwritten prescriptions, bore fruit when in 2016, the Medical Council of India ordered that “every physician should prescribe drugs with generic names legibly and preferably in capital letters”.

In 2020, India’s junior health minister Ashwini Kumar Choubey told the parliament that medical authorities in states “have been empowered to take disciplinary action against a doctor for violating the order”.

But nearly a decade later, Mr Chilukuri and other pharmacists say that badly-written prescriptions continue to arrive at their shops. Mr Chilukuri sent the BBC a number of prescriptions he’s seen over the past few years that even he could not decipher.

Ravindra Khandelwal, the CEO of Dhanwantary – one of Kolkata city’s best-known pharmacies with 28 branches covering cities, towns and villages in West Bengal and serving more than 4,000 customers daily – says sometimes prescriptions that come to them border on the illegible.

“Over the years, we’ve seen a shift from handwritten to printed prescriptions in cities, but in suburban and rural areas, most are still handwritten.”

His staff, he says, are very experienced and able to decipher most of them to ensure customers get the right medicine.

“Even so, sometimes we have to call the doctors because it’s very important for us to dispense the correct medicine.”