At a meeting with legal scholars in Berlin, JoyNews’ Jacqueline Ansomah Yeboah explores how Germany balances free speech, hate speech, and political accountability and what lessons Ghana can draw from Section 188 of Germany’s Criminal Code.

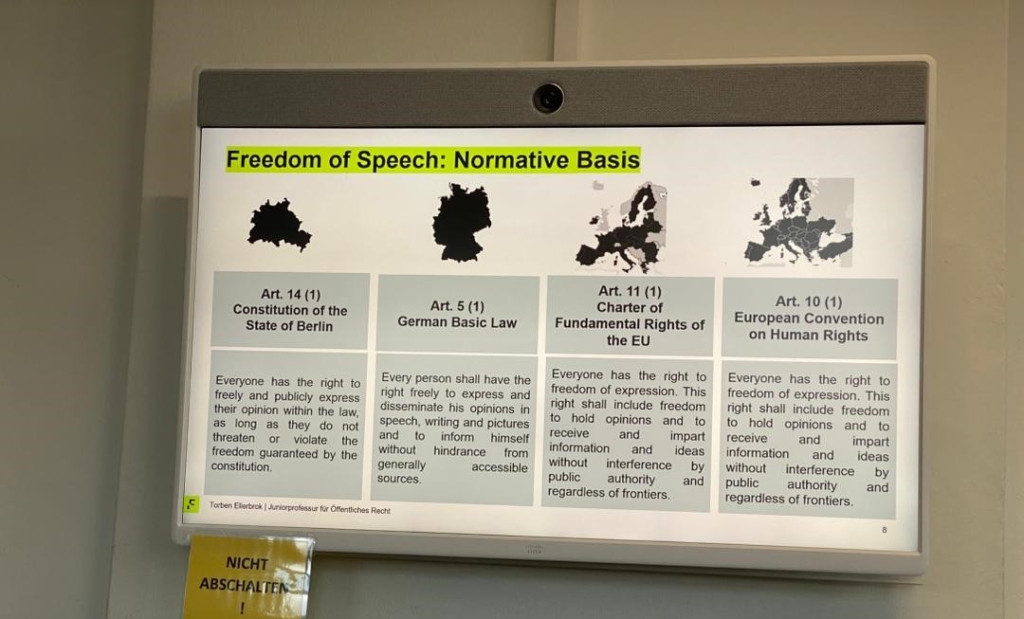

Germany is widely regarded as one of Europe’s strongest democracies, yet even here, defining the limits of free speech remains a constant struggle. During a session at the Freie Universität Berlin, Professor of public law, Torben Ellerbrok, examined how far citizens can go in criticising political leaders and where the law steps in.

A key part of that debate is Section 188 of the German Criminal Code, which makes it a criminal offence to publicly insult a political figure if the attack could obstruct their work. The penalty: a fine or up to three years in prison.

To understand its implications, JoyNews engaged Professor Torben Ellerbrok, a leading expert in Public Law.

He acknowledges the complexity: “Freedom of speech must be guaranteed for everyone. Political leaders have to be criticised, that’s essential to democracy. But they are human as well. Criminal law can help, but we must focus on protecting free speech first,” he said.

Professor Ellerbrok noted that Germany still struggles to draw a clear boundary between harsh democratic criticism and hate speech. In his words, “The line is thin and it hasn’t been fully drawn.”

Could Section 188 Work in Ghana?

Ghana’s political culture is vibrant, emotionally charged and often polarised. The idea of criminalising insults against political leaders raises difficult questions.

In response to JoyNews’ question on whether a law like Section 188 could work in Ghana, Professor Ellerbrok warned that such laws risk being misused if the boundaries are unclear.

He explained that democracies should prevent hate speech “not aggressively, but in clear situations where legal action is justified.” Anything beyond that, he said, risks criminalising public frustration a crucial part of democratic accountability.

A Growing Global Challenge

Germany’s debate is not happening in isolation. Across Europe, the rise of online abuse, misinformation and political hostility is pressuring governments to rethink how they regulate speech, especially toward public officials.

But Professor Ellerbrok’s caution is clear: protecting leaders must never come at the expense of citizens’ right to challenge power.

The Lesson for Ghana

For Ghana, a young but resilient democracy, the German experience offers a warning and a guide:

• Hate speech must be addressed, but definitions must be clear.

• Protection of leaders must not become protection of the political class.

• Free speech, even when uncomfortable, remains fundamental.

• Any legal intervention must strengthen, not weaken, democratic accountability.

As Ghana continues to confront abuses, polarisation and rising digital misinformation, the debate Germany is currently wrestling with may soon become ours as well.