At dawn in Dunkwa-on-Offin, the sound of excavators competes with the cries of roosters.

The Offin River, once a clear artery of life, is now a sludge of silt and oil. Women bend to fetch water, knowing full well it carries disease.

In the nearby clinic, the nurse keeps a running tally of ailments that were once rare—kidney failure, neurological tremors, children born with defects. She no longer asks why. The answer, villagers will tell you, is simple and deadly: galamsey.

A Country with Strong Laws but Weak Enforcement

Illegal small-scale mining has become Ghana’s ecological and legal paradox.

The state has one of Africa’s most sophisticated mining codes, anchored in the 1992 Constitution, which vests minerals in the President in trust for the people and obliges the state to protect the environment for future generations.

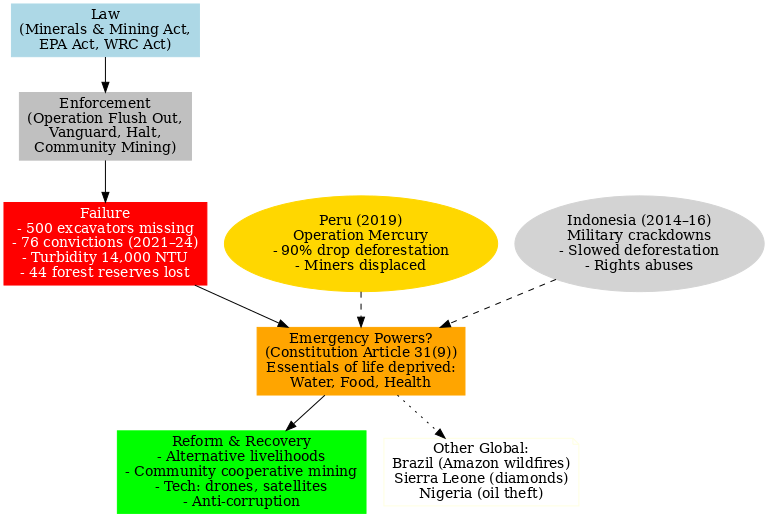

Parliament has enacted stringent laws: the Minerals and Mining Act, 2006 (Act 703), with amendments in 2015 and 2019 (Act 995), threatens illegal miners with fifteen to twenty-five years’ imprisonment and fines in the hundreds of thousands of cedis (Figure 1).

The Environmental Protection Agency Act, 2024 (Act 1124) enhances regulatory muscle. The Water Resources Commission Act, 1996 (Act 522) bars river pollution. On paper, it is watertight.

Figure 1 Ghana’s Anti-Galamsey Failures and Emergency Debate in Perspective.

The diagram shows Ghana’s shift from the Minerals and Mining Act (2006, amended 2019), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Act (1994, updated 2024), and Water Resources Commission (WRC) Act (1996) through failed enforcement (Operation Flush Out, Operation Vanguard, Operation Halt, Community Mining Scheme) marked by 500 missing excavators, 76 convictions (2021–2024), water turbidity at 14,000 Nephelometric Turbidity Units (NTU), and 44 forest reserves lost, toward Constitution Article 31(9) emergency powers, compared with Peru’s Operation Mercury (2019), Indonesia’s crackdowns (2014–2016), and global cases in Brazil, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, ending with reforms in livelihoods, cooperative mining, drones, satellites, and anti-corruption.

Crackdowns That Fizzled Out

But in practice? Between 2021 and 2024, Ghana secured just 76 convictions from over 850 galamsey cases. More than 500 excavators mysteriously vanished after seizure, some reappearing in the bush, others allegedly sold off by officials.

The Minister who led the fight admitted political complicity: an internal report accused ruling-party financiers, local chiefs, and even security personnel of profiting from galamsey. What should have been a triumph of law became a showcase of its fragility.

Successive governments have staged crackdowns. Operation Flush Out in 2006, the 2013 Inter-Ministerial Taskforce that deported 4,500 Chinese miners, President Akufo-Addo’s 2017 blanket ban on all small-scale mining, the heavily militarized Operation Vanguard and Operation Halt, and the hopeful Community Mining Scheme.

Each produced headlines and temporary lulls; each collapsed into old patterns. Soldiers took bribes, chiefs leased lands, politicians shielded allies, and miners returned. When the EPA in January 2025 ordered the cessation of all riverine mining, locals shrugged: they had heard such proclamations before.

Science as a Charge Sheet

Meanwhile, the damage multiplied. Ghana Water Company measured turbidity in rivers at 14,000 NTU, far beyond the 2,000 NTU its plants can treat. Cocoa output fell to 429,000 tonnes in 2023, barely 55 percent of target, after galamsey wiped out 100,000 acres of cocoa farms in Western North.

Mercury and arsenic levels in fish from the Ankobra and Pra tripled international safety limits, while biomonitoring revealed toxic loads in miners’ blood. Respiratory diseases in mining districts rose to 560 per 100,000, waterborne diseases to 1,180 per 100,000, heavy-metal poisoning cases to 270 per 100,000.

The Forestry Commission conceded that 44 forest reserves were degraded beyond recognition. Health worker unions declared small-scale mining “a national genocide.”

The Constitution’s Threshold

The Constitution speaks directly to this moment. Article 31(9) authorises a state of emergency when actions by any persons deprive communities of the essentials of life or endanger public safety.

In the poisoned buckets of Dunkwa-on-Offin, deprivation is undeniable. Water, food, health—all are imperilled. Public safety is threatened by militias who guard galamsey pits with AK-47s, sometimes repelling state forces.

Ghana has declared emergencies before: in Dagbon (2002) to quell violent conflict, and in 2020 under COVID-19 restrictions. Never yet for an environmental crisis. But is this not precisely what the framers anticipated?

Lessons from the Amazon

For guidance, Ghana might look to Peru. In 2019, faced with a galamsey-like scourge in the Amazon’s Madre de Dios, Lima declared an emergency and launched Operation Mercury. Over 1,200 soldiers and police stormed illegal camps, burning dredges and seizing territory.

Within a year, deforestation fell by 90 percent. For a time, rivers cleared and forests breathed again. Yet miners shifted to neighbouring provinces, and without sustained livelihoods, many returned.

Peru’s story is both a beacon and a warning: emergencies can shock the system, but unless paired with economic alternatives, the respite is temporary.

Indonesia’s Hard Lessons

Indonesia offers another mirror. In Kalimantan and Sumatra, illegal logging and river mining devastated forests. Between 2014 and 2016, Jakarta empowered military units to destroy machinery on sight, even without court orders.

Drones and satellites tracked incursions, and environmental courts upheld the measures as proportional to an ecological emergency. Rivers recovered, deforestation slowed. Yet reports of arbitrary detentions and heavy-handed tactics dogged the effort. Ghana would inherit both the power and peril of such an approach.

Global Echoes

Other nations reinforce the lesson. Brazil has repeatedly mobilized its armed forces to combat Amazon wildfires under emergency decrees.

Sierra Leone’s diamond-fueled conflict justified extraordinary crackdowns. Nigeria’s failure to formally declare an emergency over oil theft in the Niger Delta is cited as a reason its interventions faltered.

Everywhere, the same question arises: when environmental crime threatens survival, is it still mere illegality, or is it emergency?

The Case for Extraordinary Measures

In Ghana, the pros of an emergency declaration are striking. It would allow the government to impose curfews along rivers, seize excavators without legal limbo, and deploy soldiers with a clear mandate beyond the reach of local interference.

It would send an unmistakable signal of political will, restoring some trust. Most crucially, it could halt ecological freefall before water systems collapse irreversibly.

The Risks of Overreach

But the cons are sobering. Emergency powers curtail civil liberties, risk abuse by soldiers, and could devastate communities reliant on artisanal mining.

Tens of thousands would be stripped of income overnight. Unless alternative livelihoods—farming cooperatives, reformed community mining, reclamation jobs—were scaled up, unrest would follow. And unless corruption at the top is rooted out, even an emergency will falter.

Buying Time vs. Securing the Future

The lesson from Peru and Indonesia is not that emergencies fail, but that they only succeed as part of a continuum.

Emergencies buy time; reforms secure the future. Ghana must pair any declaration with transparent oversight, genuine prosecution of financiers, and long-term rehabilitation of rivers and farms.

Technology—drones, satellites, water quality dashboards—must complement boots on the ground. Chiefs and communities must be involved not as token participants but as custodians with accountability.

Back in Dunkwa, Ama Bentil dreams of the day her children can drink from the Offin without fear. In Peru’s Madre de Dios, a farmer once voiced the same hope, watching soldiers torch illegal dredges.

His river cleared briefly, then darkened again when miners returned. Ghana’s choice is whether Ama’s hope will suffer the same fate—or whether this time, the law and the Constitution will be wielded with enough courage to make the recovery last.

The writer is a lecturer at the Department of Food and Nutrition Education, Faculty of Health, Allied Sciences and Home Economics Education, University of Education, Winneba.