Over the past decade, the fashion sector has experienced a structural shift driven by ultra-fast fashion. This model is characterised by rapid production, high output, and very low prices.

A segment of ultra-fast fashion moves products from design to market within days, releases thousands of new items weekly, and prices at levels that undercut traditional apparel.

Those model choices, speed, volume, and very low-price points now shape quality and fibre mix across global flows.

While this model increases access to clothing, it has led to overproduction, declining quality, and mounting textile waste. As consumption in the Global North continues to grow, the effects are increasingly visible in the Global South, especially in second-hand clothing markets that have long supported reuse and employment.

Landfills2Landmarks works at this junction. We measure downstream effects in Ghana’s reuse markets and convert evidence into practical standards for export quality, verified end-of-life outcomes, and fair financing of recovery.

Global Production Trends

Data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD, 2023) shows that global clothing production has doubled since 2000. The average consumer now purchases 60% more garments each year and keeps them for half as long.[1]

Ultra-fast fashion brands rely on synthetic materials and offshore production to reduce costs and increase speed. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017) reports that every second, a truckload of textiles is considered unsellable. Most of which are polyester-based, a fiber derived from fossil fuels that resists decomposition.

Despite rising awareness, purchasing decisions remain primarily price-driven. The Textile Exchange Market Insight Report (2024) found that 64% of consumers in the EU and North America buy from ultra-fast-fashion brands for affordability, while only 17% consider sustainability. This consumer behaviour sustains a cycle of short-term use and high waste volumes.[2]

The Second-Hand Clothing Trade and the Global South

The second-hand clothing trade links excess consumption in the Global North with demand in the Global South. Data from the UN Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) and the European Environment Bureau (EEB) show that the EU, China, and the U.S. remain the largest exporters of used clothing, with significant flows to Ghana, Kenya, and other African markets.[3]

In Ghana’s Kantamanto Market, one of the largest second-hand clothing hubs globally, traders rely on imported clothing to support local businesses. However, the growing share of ultra-fast fashion has reduced the quality of available garments. The Ghana Used Clothing Dealers Association (GUCDA), which represents the majority of importers and retailers in the sector, in their 2024 evaluation report, based on fieldwork with retailers, the average unsellable content in imported bales is up to a maximum of 5%.[4]

The Sustainable Livelihood and Economic Impact of the Second-hand Trade

Maame is a young corporate professional in Accra with a stable 9-to-5 job. But like many young workers, her salary alone isn’t enough to meet the rising cost of living in Accra. So, she started a side business in second-hand clothing, also known as thrift.

Maame gets her stock from women at Makola or Kejetia Market, often choosing first-grade bales, higher-quality items with stronger fabric and better resale value. Her thrift business became a lifeline, supplementing her income and allowing her to build some financial security.

Now imagine what this trade means not only for young women like Maame, but also for elderly women or men who have built their entire livelihoods from it. Some have sent their children to law school, medical school, and university through this business. The second-hand economy isn’t merely about used clothes; it’s a sustainable livelihood system, a community of resilience, hard work, and dignity.

But what happens when the incoming clothes lose their quality? When ultra-fast fashion dominates the bales, both Maame and the market women lose. Their profits shrink, and their hope for a stable livelihood fades.

Ghana’s second-hand clothing economy supports extensive self-employment and micro-enterprises across importing, retail, tailoring, logistics, and materials recovery. Public finance derives revenue from imports and formalised activity within this ecosystem. L2L’s programme focuses on protecting trader cash flow and raising recovery at the end of life through standards that can scale.

Kantamanto Market in Accra stands as the archetype of this ecosystem, a bustling hub where garments are sorted, repaired, and redistributed, resilient despite recent disruptions. The trade is widely valued for providing affordable apparel, with reports suggesting that a large share of Ghanaians rely on second-hand clothing for daily needs.

Emerging Policy Developments

In June 2025, the French Senate approved a bill that proposes penalties for ultra-fast fashion and restricts certain advertising and influencer promotions. The bill proposes penalties of at least €10 per item by 2030 and restricts advertising and influencer promotions for non-compliant producers.[5] The measure has not yet entered into force and requires further approval by a joint committee and the European Commission. While it does not constitute a full ban, its signal is clear: product design and durability will face stronger policy scrutiny.

In September 2025, the EU adopted a revised Waste Framework Directive that mandates EPR for textiles across member states. The implementation track will set rules for producer financing of collection, sorting, and recycling, and will shape eco-modulation design.[6]

A key component of this directive is eco-modulation, a mechanism that adjusts producer fees based on product sustainability. Eco-modulation rewards companies whose textiles are durable, repairable, and recyclable, while penalising those producing cheap, short-lived items. The new EU directive mandates eco-modulated fees, creating a financial incentive for sustainable design.[7]

Landfills2Landmarks supports this regulatory shift but calls for stronger enforcement mechanisms. Eco-modulation works when fee bands reflect measurable outcomes. L2L’s downstream metrics: quality at point of resale, repair rates, and verified diversion are designed to inform banding so durable, repairable, recyclable textiles face lower fees and short-life items bear higher ones.

Strain on Reuse and Recycling Systems

Ultra-fast fashion’s expansion affects both primary and secondary markets. Its short product lifespan reduces the quality of goods entering second-hand streams and limits recyclability.

The European Environment Agency projects that by 2030[8], synthetic textiles will account for over 70% of global textiles that are unsellable, and most of these textiles are non-recyclable due to mixed fiber composition.

Recycling systems are not designed to handle these volumes. Blended fibers, chemical finishes, and low fabric strength hinder processing. As a result, much of this clothing ends up in landfills or incinerators in importing countries. The Changing Markets Foundation (2023) reports that second-hand imports into Kenya and Uganda are now dominated by polyester-based garments. Many cannot be reused or recycled and are either burned or dumped, causing local pollution and microplastic contamination.[9]

Strengthening Responsibility and Circularity

The core issue lies in production and design, not only consumption. Fast fashion reflects a structural failure to design for longevity and reuse. A sustainable textile system requires alignment between design standards, production practices, and management at the end of life, with incentives that reward durability and verified recovery.

Landfills2Landmarks supports a cross-border standards and financing track that links production choices to results where goods are handled. This includes EPR schemes with transparent reporting and independent verification, honest descriptions of material composition, and producer funding committed to sorting, repair, and diversion capacity in importing markets. Investment in local reuse infrastructure remains essential. Repair centres, sorting facilities, and digital resale systems extend garment life and create employment, but their effectiveness depends on the quality of textiles entering the chain. Circularity does not operate on poor-quality inputs.

A pressing gap is the absence of consistent export quality and sorting rules. Landfills2Landmarks supports an export quality and sorting protocol shaped by what importers, trader associations, and retailers manage in practice. It defines bale grades, sets clear defect thresholds, requires plain descriptions of material composition, and mandates a simple dossier that travels with the goods so quality can be verified on receipt. Roles and duties are specified for collectors, graders, exporters, importers, and market associations, and training, supervision, and record keeping are embedded.

Regular independent audits and certification protect responsible actors and deter substandard consignments. Where labels are missing or fibres are mixed, composition is evidenced through documented sampling at consignment level with declared confidence ranges, trained grader assessment, and simple bench tests where appropriate.

Unknown or mixed fibres are recorded transparently using agreed classes such as predominantly synthetic or predominantly natural, with notes on features that affect reuse and recycling. Participants join a pilot cohort, accept independent spot checks, and publish cohort-level results. Performance informs producer responsibility fees and guides investment in repair, take back, and diversion, without naming and shaming.

Landfills2Landmarks Position

Landfills2Landmarks supports a cross-border, accountable system for textiles that places clear responsibility on producers and equips importers, traders, and retailers to repair, reuse, and recirculate garments. We focus on what can be operated now.

Traceability that follows consignments from entry through first sale, repair, and return. A buy-back credit ledger that settles unsold items to keep traders liquid and reveal quality patterns. A clear export quality and sorting protocol with roles, documentation, and an independent audit, so quality is not left to custom on the day.

Our policy is evidence-led. Cross-border EPR with transparent reporting and independent verification should drive eco-modulation that lowers fees for durable and recyclable textiles and raises them for short-life items. Producer funding should build sorting, repair, and diversion infrastructure where goods are handled at scale. Public interest sits at the centre. Livelihoods, job creation, and environmental stewardship are advanced together, so circularity contributes to social equity and climate goals rather than shifting costs onto receiving communities.

Landfills2Landmarks’ Work In Ghana

Landfills2Landmarks began its programme in Ghana, a major hub for the second-hand clothing economy. From this base, we are piloting three connected programmes that turn market activity into measurable data. A traceability system follows consignments from entry through first sale, repair, and return, recording time to sale, reasons for return, and simple durability checks.

A buy-back credit ledger settles unsold items on agreed terms, maintains retailer liquidity, and surfaces quality signals for importers and exporters. A research and policy track publishes cohort-level dashboards each quarter to inform export standards and producer responsibility fees. We deliver this with trader associations, importers, and public agencies, and we invite exporters and platforms to join and co-publish results. Initial indicators include shares sold within 7 and 30 days, repair rate, return rate by category, and net credit settled per cohort.

This programme is early stage and limited in scope. Current cohorts do not represent the entire market, and results are indicative. Methods, sampling, and definitions are being refined with partners. Landfills2Landmarks runs this as a public interest programme.

Data is published at cohort level, not as league tables, and individual participants are not named in public outputs. No commercial resale of data occurs, and any producer contributions are directed to agreed activities such as repair, sorting, and diversion capacity. The purpose is to generate reliable evidence that can support standards, fee banding, and investment decisions.

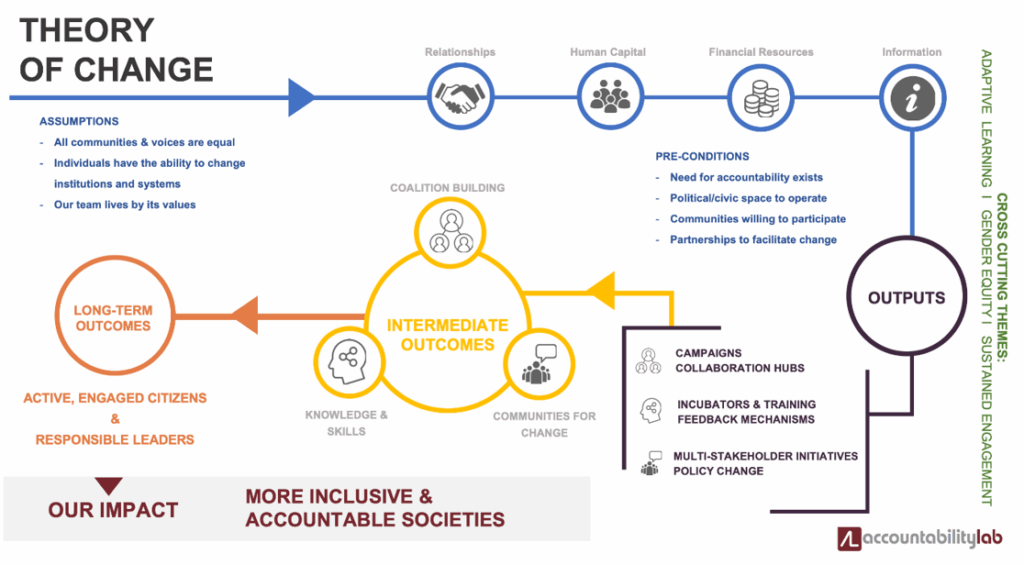

Applying a Theory of Change to the Textile Crisis

Drawing from this framework, a theory of change for addressing the fast fashion fallout begins with preconditions that include space for frank discussion on trade and waste, and communities ready to participate. Inputs then focus on funding for traceability technology, training for traders, and coalitions for policy advocacy. These produce tangible outputs, such as buy-back pilots in markets like Kantamanto, cross-border EPR rules that place costs in line with design choices, and hubs for sorting and repair that lift low-grade bales into saleable stock.

Intermediate outcomes follow: stronger skills for waste pickers and retailers, more inclusive voices in policy forums, and feedback loops that allow markets to signal low-quality imports. Over time, this enables long-term gains, with more durable clothes circulating longer, livelihoods holding steady, and a circular economy in which the Global South is not left bearing the cost of overconsumption elsewhere. The impact is accountable supply chains that cut pollution, expand decent work, and make reuse the norm.

This model depends on testing assumptions in public. Cohort methods, sampling notes, and limitations are published, and parties commit to learning loops that adapt the programme as evidence accumulates, including whether brands contribute under eco modulation and whether local leadership can enforce rules without loopholes.

L2L’s work is to move the system from narrative to operating procedures. We convene exporters, platforms, traders, and regulators to raise quality at source, finance recovery at the end of life, and protect livelihoods. Collaboration on standards, data, and pilots is how we get there.

[1] https://www.textiletoday.com.bd/apparel-and-textiles-trade-value-dropped-by-over-12-in-2023-unctad

[2] https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy

[3] https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-05/ExecutiveSummary-Improving-sustainability-usedclothing.pdf

[4] https://www.textilerecyclingassociation.org/press/ghanaian-used-clothing-dealers-association-report/

[5] https://www.euronews.com/my-europe/2025/06/11/french-senate-backs-law-to-regulate-ultra-fast-fashion-giants-shein-and-temu

[6] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20250905IPR30172/parliament-adopts-new-eu-rules-to-reduce-textile-and-food-waste

[7] https://rev-log.com/textile-epr-explained-essential-faqs/

[8] https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/newsroom/news/consumption-of-clothing-footwear-other-textiles-in-the-eu-reaches-new-record-high

[9] https://changingmarkets.org/report/trashion-the-stealth-export-of-waste-plastic-clothes-to-kenya/