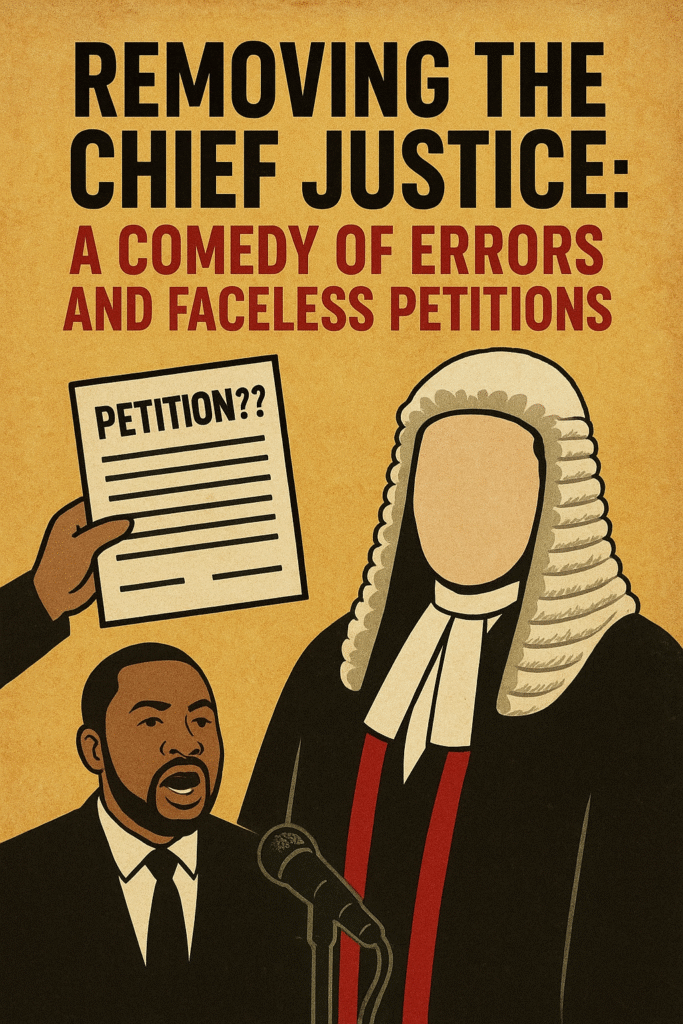

Ghana is buzzing with talk of removing the Chief Justice. The Attorney General wants it. Prof. Kwaku Azar supports it. Oliver Barker-Vormawor is tweeting fire emojis about it. And Thaddeus Sory? He’s hunting for legal technicalities like a detective in a courtroom thriller. Meanwhile, faceless petitions float around, accusing the Chief Justice of mysterious travel expenses. It’s a drama so bizarre, it could have been scripted by a Netflix writer—but sadly, it’s all very real.

1. Faceless Petitions and Suspicious Claims

Adding to the drama are petitions claiming misconduct, including alleged irregularities in travel expenses. Yet the people behind these petitions are unknown—faceless, nameless, and largely unverifiable. When anonymous allegations form the core of a case for removing the head of the judiciary, we’re playing with fire. The rule of law cannot bend to rumors or ghost-written complaints. If travel expense disputes become grounds for dismissal, tomorrow any judge could be threatened by anonymous accusations and public pressure.

2. The Constitution Isn’t a Suggestion Box

Article 146 of Ghana’s Constitution is crystal clear: the Chief Justice can only be removed for stated misbehavior or incapacity. Not “unpopular rulings.” Not “anonymous petitions.” Not “the Attorney General feels strongly.” Unless there is clear, evidence-based misconduct, removal is unconstitutional. Full stop.

3. Judicial Independence Is Non-Negotiable

The framers understood a simple truth: judges must be insulated from political winds. If removal becomes a tool for responding to faceless complaints or fleeting public anger, every Chief Justice—and every judge—will serve at the pleasure of politicians and rumor-mongers. Imagine writing a ruling while worrying that some anonymous petition could cost your job. That isn’t justice; it’s chaos with robes.

4. Bad Precedent Is Worse Than a Bad Judge

Prof. Azar argues for removal as if it were a corrective measure. But precedent matters more than personalities. Once you lower the bar for removing one Chief Justice—even on shaky grounds like unverified travel claims—you create a dangerous template. Today it’s this Chief Justice; tomorrow it could be another who dares rule against a powerful interest. The judiciary becomes a revolving door—and democracy becomes a game of musical chairs.

5. Accountability Has Proper Channels

Oliver calls for accountability, and he’s right that judges must answer for misconduct. But accountability already exists: judicial review, impeachment processes, internal ethics bodies, and public scrutiny of rulings. Thaddeus Sory’s push to exploit technicalities—looking for loopholes to remove the Chief Justice—does not meet the constitutional threshold. Legal technicalities cannot override clear procedural safeguards. Accountability is not the same as political decapitation.

Conclusion: The Rule of Law or the Rule of Rumor?

The Attorney General and his allies may be loud, but their case is legally hollow. Faceless petitions, unverified claims about travel expenses, and technicality-hunting by Thaddeus Sory do not override constitutional safeguards. The judiciary requires independence, not interference. Ghana requires stability, not spectacles fueled by rumor.

If we truly care about accountability, we must follow the law as written. Anything else is not accountability—it’s improvisation. And Ghana’s Constitution is not a stage for ghost-written complaints, viral gossip, or technicality hunts.

We love fooling around, but this is clearly political. The NDC is shamelessly trying to turn the judiciary into a playground for their power games.

By

Simprimoo Gyebi De first.

Social Commentator.

Email. agyei.gyebi123@gmail.com