Minister for Communications, Digital Technology and Innovation, Sam George, has called for an uncompromising national action against illegal mining, popularly known as galamsey.

According to him, the death of the late Defence Minister, Dr Kofi Omane Boamah, along with seven other persons in the line of duty, should serve as a call to action.

Speaking on Joy FM’s Super Morning Show on Tuesday, August 12, Mr George reaffirmed his personal and political resolve to intensify the fight against galamsey, describing it as a non-negotiable national emergency.

“My belief and resolve in the fight against galamsey is as strong as it has ever been,” the Minister declared.

“I lost my big brother, Kofi Omane Boamah, and seven other sons of our land because of galamsey. The least we can do in their memory is to wage an all-out war on it.”

Highlighting the late Defence Minister’s unwavering commitment to the cause, Mr George revealed that the former Defence Minister had a long-standing aversion to flying, but broke that habit solely for a mission against illegal mining.

“Omane had refused to sit in helicopters or planes since he became Defence Minister. This was literally one of the only times he agreed to fly – and it was because of galamsey. That should tell you how deeply invested he was in this fight,” Mr George noted.

The Minister also indicated that his brother had entrusted him with a key role in implementing technological and strategic approaches to combat the illegal mining scourge.

“As Communications Minister, Omane had given me an assignment in the fight against galamsey,” he said. “He believed in using both conventional methods and digital technology as part of a holistic solution.”

He reiterated detailed plans to confront illegal mining head-on, plans he believes must now be brought to fruition in honour of those who lost their lives in the fight.

The Minister drew parallels with the nation’s inaction following the murder of Major Maxwell Mahama, on Monday, May 29, 2017. Who was also killed during an anti-galamsey operation.

“It would be a disservice to the memory of our colleagues if we do not take decisive action. We failed to act meaningfully after the tragic death of Major Mahama, and now eight more brave souls have been lost. How many more are we waiting for?”

He emphasised the urgency of government intervention, warning that further inaction would be a betrayal of those who have already paid the ultimate price in the ongoing battle to safeguard Ghana’s environment and future.

“There must be decisive action, it’s non-negotiable,” he said.

Background

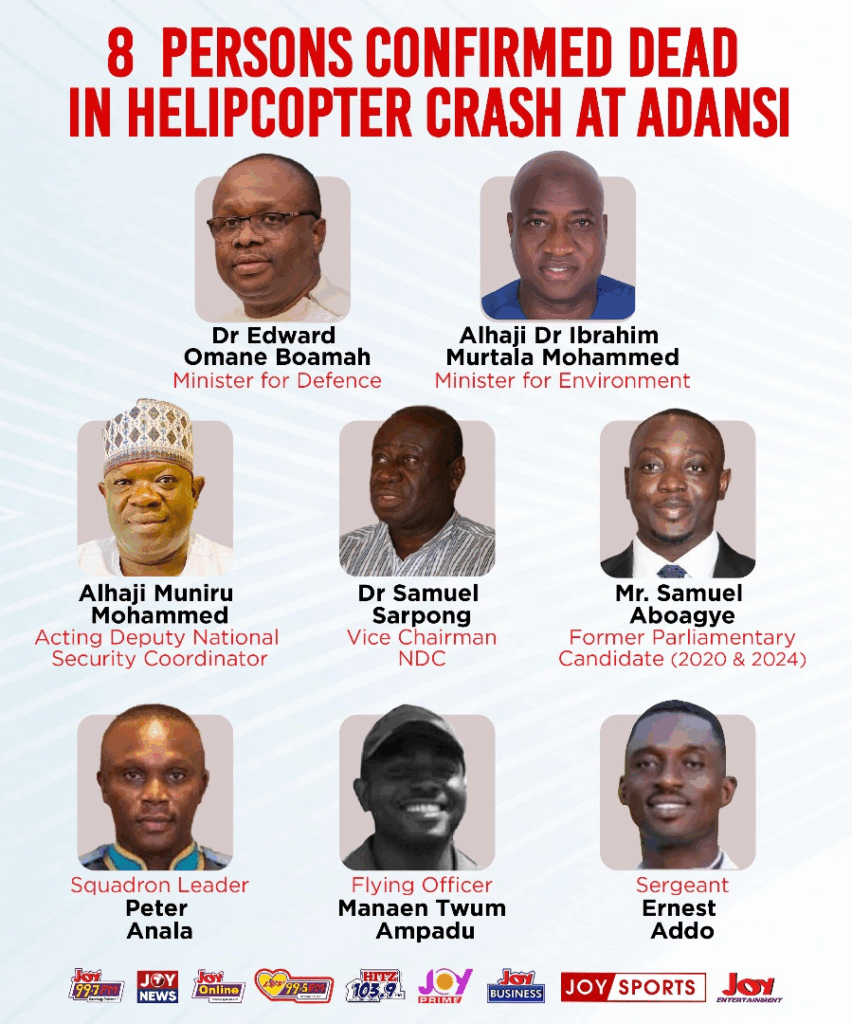

The helicopter crash that occurred in the Ashanti region claimed the lives of eight distinguished individuals who were attending the launch of an anti-galamsey initiative in Obuasi.

Below is a list of the victims of the tragic crash:

- Dr Edward Omane Boamah, Minister for Defence

- Alhaji Dr Ibrahim Murtala Mohammed, Minister for Environment

- Alhaji Muniru Mohammed, Acting Deputy National Security Coordinator

- Dr Samuel Sarpong, Vice Chairman of the National Democratic Congress (NDC)

- Mr Samuel Aboagye, Former Parliamentary Candidate

- Squadron Leader Peter Bafimi Anala

- Flying Officer Twum Ampadu

- Sergeant Ernest Addo