Corruption remains Ghana’s greatest governance challenge. Year after year, reports from the Auditor-General, the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) of Parliament, and other institutions expose the billions of cedis lost through embezzlement, inflated contracts, and abuse of office.

This bleeding of national resources denies citizens access to quality education, healthcare, jobs, and infrastructure. It also erodes public trust, making our democracy weaker and fragile.

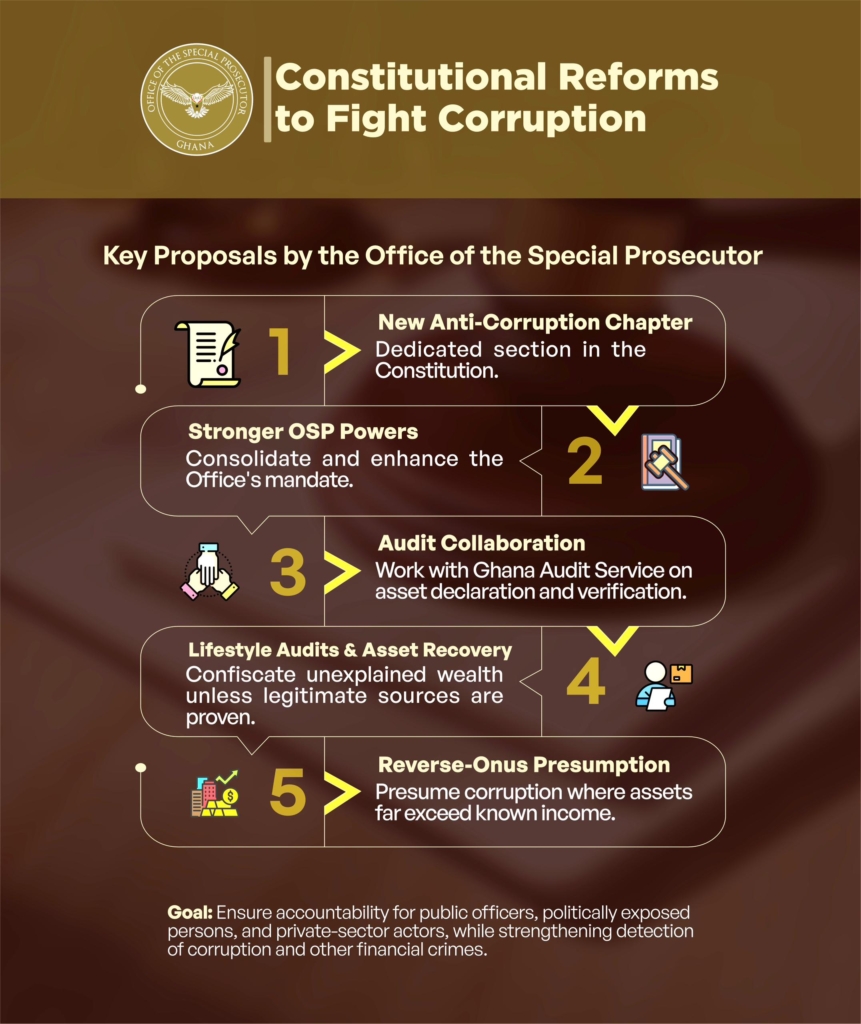

Against this background, the Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) has proposed bold constitutional reforms to strengthen the fight against corruption.

Among its key proposals are the creation of a new anti-corruption chapter in the Constitution, stronger OSP powers, collaboration with the Ghana Audit Service, lifestyle audits and asset recovery, and a reverse-onus presumption where unexplained wealth is treated as corruption unless proven otherwise.

Let me be quick to add that these proposals have been suggested by CSOs like The Bright Future Alliance (TBFA), some political and religious leaders, institutional heads, the media, and well-meaning Ghanaians for many years.

These reforms deserve serious national consideration.

Why the Proposals Make Sense

The 1992 Constitution already has provisions on accountability, including asset declarations (Article 286) and conflict of interest (Articles 284–288). Yet, enforcement has been weak, with loopholes easily exploited. A new anti-corruption chapter would elevate the fight against corruption to a constitutional imperative, similar to what Kenya achieved in Article 79 of its Constitution.

Stronger OSP powers would consolidate the office’s mandate, reduce institutional bottlenecks, and allow high-profile corruption cases to be prosecuted without undue political interference. Collaboration with the Ghana Audit Service could bridge the current implementation gap, where audit reports expose financial malfeasance but hardly lead to prosecutions or asset recovery.

Lifestyle audits and asset recovery provisions would finally breathe life into Article 286 by forcing public officials to justify their wealth. Ghana is already a signatory to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC), which obliges states to adopt such measures. The reverse-onus presumption, though controversial, has the potential to deter the accumulation of unexplained wealth by public officials — a phenomenon that has become all too common in Ghanaian politics and even in private lives.

In short, the OSP’s proposals show a genuine desire to deal decisively with corruption — the cancer that drains our nation.

The Risks We Cannot Ignore

But these reforms also raise serious constitutional and governance concerns. Ghana’s Constitution guarantees the presumption of innocence under Article 19(2)(c). A reverse-onus presumption, which shifts the burden of proof to an accused person, could clash with this principle and face constitutional challenges in court.

There is also the danger of abuse of power. If lifestyle audits and reverse-onus provisions are applied selectively, they could become tools for political witch-hunting rather than instruments of justice.

Implementation is another concern. Ghana does not suffer from a lack of laws; it suffers from weak enforcement and limited political will. The 1992 Constitution and the OSP Act, 2017 (Act 959), already provide powerful tools, yet corruption cases rarely result in convictions — either because of poor work by prosecutors or lack of support from the judiciary — and often meet prolonged delays in the courts. Adding more laws without addressing the culture of impunity may not change much.

The Way Forward

Ghana needs bold reforms, but they must be constitutional, fair, and enforceable. A new anti-corruption chapter and improvements in asset declaration laws are welcome, but they should be carefully designed to avoid undermining constitutional rights. Lifestyle audits and asset recovery should be implemented under strict judicial oversight to prevent abuse. Collaboration among institutions — OSP, Auditor-General, PAC, EOCO, and CHRAJ — must be strengthened, not duplicated.

Most importantly, political leaders must demonstrate genuine commitment by allowing institutions to work independently, free from interference. Without this, even the strongest laws will be reduced to paper tigers.

Corruption has cost Ghana too much already. We cannot continue on this path if we truly want development, prosperity, and justice. The OSP’s proposals provide a chance to rethink our approach. If carefully refined and implemented by the state, they could mark a turning point in our national struggle. But if politicized, they could do more harm than good.

The time to act is now — boldly, wisely, and in the supreme interest of Ghana.