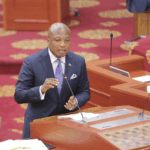

The Chairman of the Constitution Review Committee has warned against rushing reforms to Ghana’s judicial structure without firm data to justify the changes, particularly proposals affecting the Supreme Court.

Prof Henry Kwasi Prempeh, speaking on Joy News, stressed that any attempt to alter the appellate structure must be grounded in evidence rather than assumptions.

He said reforms without statistics amount to a gamble with the justice system.

“You made a very important point about cases getting overturned, and in fact, this is where statistics is important,” he said.

According to him, the country must first establish reliable data on how often cases are overturned between the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court.

“I would actually hope that we would get to a point where we have data to show the rate of overturned between the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court,” he said, describing such information as “an important statistic we must have before we make a full move on that one.”

Prof Prempeh explained that the direction of reform would depend heavily on what the data shows.

“Because if the statistics show that that case is 90% of the cases are overturned, then we are in trouble,” he said. “On the other hand, if they show that 90% are affirmed, then that layer is just delaying.”

He said the courts must rely on their own records to guide the reform process.

“I hope that the courts have the records and that at the appropriate stage in the process we can look at those records and say, look, the rate of overturn is so high that that layer is still necessary,” he noted.

For Prof Prempeh, this is not a decision to be taken lightly. “So it’s not one of those decisions I think that we should make easily,” he said.

He acknowledged, however, that concerns about delays in the justice system were legitimate. “The idea was that cases were backing up. Too many cases are ageing in the system. Justice deleted. Justice denied,” he said.

He added that prolonged litigation harms ordinary citizens. “It’s not fair to the litigants for cases to be there for 10 or 20 years,” he said.

According to him, stakeholders identified jurisdictional bottlenecks as a key cause of delays. “What is slowing down the process? And they said, well, jurisdiction is one of them. Everything goes up to the Supreme Court,” he explained.

That concern, he said, led to proposals aimed at managing the Supreme Court’s workload.

“So it’s okay, then let’s, let’s put in some of these reforms to make sure that we can at least control the volume of the load that’s going there,” he said.

Prof Prempeh was clear that the committee’s proposals did not emerge in isolation. “These are things that we came to these decisions from real engagement with the judge,” he said.

He disclosed that the committee held extensive consultations across the judiciary.

“We met the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court, the district court, the circuit court, and we had a dialogue with them around these issues,” he said.

Despite the pressure to act, Prof Prempeh insisted that reform must be deliberate, evidence-based, and carefully sequenced, warning that without data, changes to the Supreme Court risk doing more harm than good.