Ghana, that tranquil republic known for peace, tolerance, and occasional hypertension, has awakened to a curious spectacle: our senior high schools have quietly transformed themselves into religious battlegrounds. While the rest of the world debates artificial intelligence, climate change, and the cost of sending humans to Mars, Ghana is debating the cost of allowing a Muslim girl to wear her hijab while conjugating French verbs. In some of our schools, even blinking in the direction of your own religion now requires exeat.

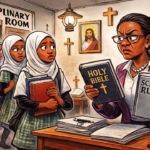

Take Wesley Girls High School, for instance—a school so famous that even its dining hall has pedigree. Once upon a serene morning, the school reportedly reminded its Muslim students that the path to “excellent character formation” included compulsory attendance at Christian services. Not just optional fellowship ooo—compulsory, as if Jesus Himself had sent a memo to the headmistress instructing her to ensure all daughters of Abraham report for devotion by 4:30am sharp, hymnbook in hand. Fasting? That too raised suspicion. A girl skipping breakfast for Ramadan was interrogated like she was trying to smuggle contraband faith across the dining hall.

In the midst of this, the Constitution arrived at the school gate—late, confused, and without exeat. Article 21, that gentle old prefect of religious freedom, attempted to enter the assembly hall, only to be told by the school authorities that unless it could prove it was in the original 1876 Methodist blueprint, it had no business interfering with discipline. Ghana’s Constitution is a day student after all; school doctrine is the permanent boarder.

Then arrived the Minister of Education, breathing edicts and warnings with the enthusiasm of a prophet descending from Mordechai Hill. His statements—issued with biblical urgency—sounded less like policy and more like the Ten Commandments receiving a budget revision. He seemed determined to prevent a full-scale religious uprising, though his pronouncements carried the unmistakable tone of a man tired of refereeing spiritual tug-of-war matches between parents, pastors, imams, and alumni groups who behave like UN observers in school uniform.

And just when the dust seemed ready to settle, the Supreme Court entered the classroom like a no-nonsense headmaster. They summoned the school’s Board of Governors to answer for these allegations. The Board, suddenly shy, shuffled forward like Form One students who had been caught climbing the school wall to buy waakye during prep time. Meanwhile, the Constitution—still standing in the corridor—peeped inside and whispered, “Ei, so you people really don’t rate me?”

Parents too have taken the matter personally. The National Council of PTAs, usually quiet except when they are announcing levies, has suddenly discovered its voice. They warned about “religious bias” in schools, speaking with the righteous indignation of parents who haven’t attended a meeting in five years but now feel spiritually obligated to defend the republic’s moral fabric. They want unity, harmony, peace—everything except contributing their ward’s unpaid PTA dues.

Mission schools, to be fair, are proud institutions with noble pasts, built on foundations of love, tolerance, and evangelism. But somewhere along the line, “love thy neighbor” has been replaced with “love thy neighbor, but only if she joins morning devotion.” One wonders: if Jesus Himself appeared at Wesley Girls today wearing His traditional Middle Eastern robe, would He be allowed to wear His traditional robes?

Through all this, the students have become accidental hostages in a holy Cold War. Muslim girls navigate their faith the way undercover agents exchange secret codes. Christian girls observe the tension with the ambience of referees at a match nobody wants to officiate. Teachers, exhausted from supervising morning worship, afternoon prep, and evening prayer, sigh heavily and mutter, “This one dier, only God can mark it.”

The tragedy hiding behind all this comedy is that Ghana’s religious harmony—the thing we boast about during Independence Day speeches and international conferences—is being kneaded into confusion at the dining tables of our senior high schools. On the surface, we play the tolerant nation; underneath, some of our schools are quietly running denominational immigration checkpoints.

Yet the solution is not complicated. Let mission schools preserve their values, their hymns, their mottos, and their heritage—but they cannot turn themselves into compulsory conversion centers. Faith is a personal journey. Education is a public right. When the two collide, common sense—not crusade—should lead.

And so, may Ghana find its way back to the peaceful coexistence we proudly sing about. May every student worship without fear. May the Constitution finally find a seat in the assembly hall without being asked, “Who invited you?”

And above all, may common sense, that endangered species in our public life, descend upon us with the speed and urgency of a headmistress closing the school gate at 8am.

About the Author:

Jimmy Aglah is the creator of the Republic of Uncommon Sense, a writer known for his sharp, humorous commentary on Ghanaian life, governance, and the everyday madness we all pretend to understand. He is also the author of Once Upon a Time in Ghana and The Price of Gold: The Fight for Sikakrom’s Soul.