At the confluence of the White and Blue Nile, the Sudanese capital Khartoum once stood as one of the most significant political, economic, and cultural centers in both the Arab and African worlds.

For centuries, it served as a vital cultural and commercial hub.

But the devastating war that erupted in mid-April 2023 has left the city in ruins, indifferent to its long and storied heritage.

In the latest developments, panic and chaos swept through Bashair Hospital in southern Khartoum when a soldier affiliated with the Joint Forces (Minawi faction) threatened to blow up the hospital with a hand grenade after learning that one of his wounded comrades had died.

The threat triggered a mass exodus of medical and administrative staff, patients, and their families.

The incident followed armed clashes between members of the Joint Forces and the Sudanese army near the Fish Market, north of the hospital – further heightening tension in the area, according to Al-Mashhad al-Sudani newspaper.

Despite an order by Army Commander Abdel Fattah al-Burhan to withdraw all armed formations from the capital, many of the armed movements and allied fighting groups have refused to leave Khartoum, leaving key facilities exposed to violations and unrest, the paper reported.

Mounting and Persistent Disputes

This defiance of al-Burhan’s decision reflects a broader pattern of ongoing disputes. In August, the Joint Forces – comprising armed factions that signed the Juba Peace Agreement – announced their rejection of al-Burhan’s decree placing all auxiliary forces under direct army command, as stipulated by the Armed Forces Act of 2007 and its amendments.

Idris Laqma, a leader in the Justice and Equality Movement, declared on Facebook that the Joint Forces would not comply with al-Burhan’s order, stressing that their relationship with the army is governed solely by the security arrangements protocol of the Juba Peace Agreement, signed in 2020.

He explained that al-Burhan’s decree primarily targets new formations that emerged after the war began – such as Sudan Shield Forces, Al-Baraa ibn Malik Battalions, and the Popular Resistance – groups that are not covered under the Juba Agreement but operate as pro-army militias.

This divergence of positions highlights the deep complexity of Sudan’s military landscape, where the interests of armed movements bound by international accords intersect with the military leadership’s push for unity and discipline, according to Al-Taghyeer newspaper.

Tribal Conflicts and the Fueling of Strife

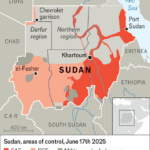

Amid these tensions, tragic tribal clashes erupted in Karnoi, Darfur, leaving 19 people dead, including prominent tribal leaders.

The fighting broke out between two rival clans of the Zaghawa tribe and spread to the towns of Abu Qumra, Tandubaya, and Abuliha, causing significant material losses, including the burning of several villages under the administration of tribal chief Shartai Adam Sabi.

According to media reports, local Zaghawa leaders rejected the presence of the Joint Forces – which fight alongside the Sudanese army – in Karnoi, after members of the unit were accused of taking sides in the conflict instead of mediating between the rival clans.

Al-Jamaheer newspaper reported that Zaghawa elders informed Sudanese army commanders in Karnoi of their refusal to allow any Joint Forces personnel to remain among the troops responsible for separating the combatants.

The report added that army command ordered the withdrawal of the Joint Forces from the conflict zone, instructing them to leave immediately. However, the Joint Forces refused to comply, sparking verbal altercations between leaders of both sides, according to the same source.

The Darfur Regional Government expressed its “deep sorrow and regret” over the deadly events, offering condolences to the victims’ families.

It “strongly condemned the attacks and the incitement of strife among the region’s people,” holding those responsible for planning and execution “fully accountable before the law.”

The government affirmed it was “taking the matter with utmost seriousness” and following up through its security and legal institutions “to ensure that every perpetrator is held accountable, regardless of position or affiliation.”

Initial investigations, the statement noted, point to the involvement of influential figures in Port Sudan’s ruling authorities, alongside certain allied armed movements, in fueling and steering the conflict to serve narrow political agendas unrelated to the interests of Darfur’s residents.

Enduring Marginalization

Meanwhile, Sudanese reports indicate that the army continues to exploit the Zaghawa, pitting them against one another while treating them as second-class citizens.

Despite fighting in its ranks during the ongoing war, Zaghawa communities have repeatedly suffered airstrikes by the Sudanese Air Force – particularly across the Darfur region.

This persistent mistreatment drove the Zaghawa “Um Kamlati” clan to seek protection by aligning with the Founding Sudanese Alliance, declaring allegiance in hopes of being recognized as full citizens with equal rights.

In August 2025, the Supreme Council for Civil Administrations, headed by Dr. Hudhaifa Abdullah Mustafa Abu Nuba, met with a high-level delegation from the Zaghawa Um Kamlati, led by Prince Al-Sawi Ali Hamad and including twenty local, youth, and community leaders.

Abu Nuba stated that the newly announced Government of Peace and Unity “represents all regions and components of Sudan” and aims to counter “misleading propaganda” while granting the revolution a “firm popular legitimacy.”

He added: “For the first time, we bless a political alliance that unites genuine forces of change – the Founding Alliance – and we pledge to move forward to fulfill the people’s demands, end marginalization, and stop the elites and cliques that have squandered Sudan’s hopes.”

A New Sudan

After decades of exclusion and oppression, the Founding Alliance Government has adopted a charter seeking to affirm Sudan’s national identity and ensure fair distribution of power and wealth – laying the foundation for a cohesive and progressive society.

The charter aims to end war and division, offering solutions to Sudan’s long-standing governance crises, which past agreements failed to address due to military dominance.

It envisions a secular, democratic, decentralized state that recognizes diversity and bans the formation of any political party or organization based on religion or race. It also recognizes the right to self-determination in cases where secularism is rejected or any supra-constitutional principle is violated.

The document emphasizes equal citizenship, a national identity rooted in diversity, and the management of the national capital as a reflection of Sudan’s pluralism.